The concept Retrospective has existed almost forever, but not always

with that name. As long as humans have existed we have looked back at an

activity together, to try to learn from it. After a hunt, after a birth,

after a game, after surgery, etc.

Norman Kerth was the first to name it “Retrospective” in the IT world,

in his book: Project Retrospectives – a Handbook for Team Reviews from

2001. He described a formal method for preserving the valuable lessons

learned from the successes and failures of every project. With detailed

scenarios, imaginative illustrations and step-by-step instructions, this

book started my journey as a retrospective facilitator. I loved the idea

and I began implementing it, first in my own team, then in other teams and

later, outside my organization. The activities “Prime Directive”,

“Developing a Time Line”, “I’m Too Busy” and other activities are from

his book.

Later, Diana Larsen and Esther Derby wrote the book: Agile

Retrospectives – Making Good Teams Great. This introduced shorter

retrospectives that would fit into agile processes. This was a game

changer for me. Their book helped me to plan shorter, more efficient

retrospectives, but also contains tools for the facilitator that helped me

with the actual process of planning the retrospectives in a more efficient

way.

Before Norm Kerth’s book, we only knew about post-mortems. These are

longer reflections conducted after something has gone wrong. Post-mortems

are very useful as a tool for learning from mistakes. Done right, they can

have a healing effect on the people involved, but are not the same as

retrospectives. We do retrospectives, even if things are going well. This

is why the subtitle of Derby Larsen’s book is “- making good teams

great”.

But, my practical experience with retrospectives also showed me how

easily a retrospective can be inefficient. If you don’t follow the idea of

a retrospective and only go through the motions, you will waste time. Due

to the popularity of agile methodologies, retrospectives have become very

widespread. This success has become a problem for retrospectives. Everyone

has to have them, but they do not spend the time to learn how to

facilitate them in the right way. This has led to many unconstructive, and

sometimes even harmful, retrospectives. When people claim that

retrospectives are a waste of time, I often agree with them, when I hear

how they do it. After some years I started to notice patterns in what went

wrong, also in the ones facilitated by me.

A story from Denmark

An organization had decided to be more agile in their way of developing

software. As a part of that they introduced retrospectives as a means to

learn. Some of the team members felt that the retrospectives were “in the

way” of “real” work. They suggested that they could be shorter than the 90

minutes booked for them. Since the facilitator was not very experienced in

retrospectives, she decided to accept.

To spend as little time as possible, they shortened them down. This had

many negative consequences. Let us focus on one here, an anti-pattern I

call Wheel of Fortune. In a real-world wheel of fortune you sometimes

get a prize, and sometimes you lose. Winning or losing is random, and you

aren’t doing anything to improve the odds. This can happen in a team’s

retrospective as well.

The facilitator decided to use the popular “Start, Stop, Continue”

activity to gather data. But to save time, they skipped generating

insights, which is one of the 5 stages of a retrospective. Instead they

jumped from gathering the data to deciding what to start doing, what to

stop doing, and what to continue doing.

For this activity, the facilitator put up three posters, one with the

word “Start”, one with “Stop”, and one with “Continue”. She then asked the

team to write post-it notes and stick them on the posters. One of the

notes read “Start pair programming”, another “Stop having so many

meetings”. The team could create action points out of these: “Three hours

of pair programming, three days a week”. And “no meetings on Wednesdays

and never meetings after lunch”. And in 20 minutes, the retrospective was

over!

This way of holding a retrospective can have dire consequences. If the

post-it notes only show solutions to symptoms, not the actual problems,

you can only fix the surface. Perhaps the reason for the team not having

pair programming is not that they forget, but that there is not enough

psychological safety. In this case, pushing them to schedule it in the

calendar will not help. Either they will still not do it, or they will do

it and people will feel uncomfortable and leave the team, or even the

company.

Another cause for not having pair programming, could be that they do

not know how to do it in a remote setting. Again, this is a problem that

is not solved by putting pair programming in the calendar.

The same applies to the note about meetings. The problem with the

meetings might be the quality and not the quantity. In that case, having

fewer meetings will not solve the problem, only make it less obvious. When

teams ask for fewer meetings, it is often improved meeting hygiene that

can solve the real problem.

Wheel of Fortune

When a team “solves” symptoms instead of problems, the problems will

still be there, and they will show up again. As in a real Wheel of

Fortune they might get lucky. Perhaps some of the things they solve might

have been the real problems. But often we only see the symptoms and we

rush to ‘solutions’ that don’t address root causes. The result is that

even these short retrospectives feel like a waste of time, because it is a

waste of time to discuss and react only to symptoms.

An anti-pattern must have a refactored solution, a description

of a solution that is better than the antipattern solution. In this case,

the refactored solution is to make sure to generate insights before you

decide what to do. Before you jump to conclusions. You can do this with a

simple discussion about the issues that come up. Or with a “5 whys” interview. If it looks like a complex problem,

a fishbone analysis might be useful.

Examples of complex problems are “missing a deadline”, or “not following

the peer review process”. Stated like this, they sound simple, but the

short description hides a complexity: These problems can have many

different causes.

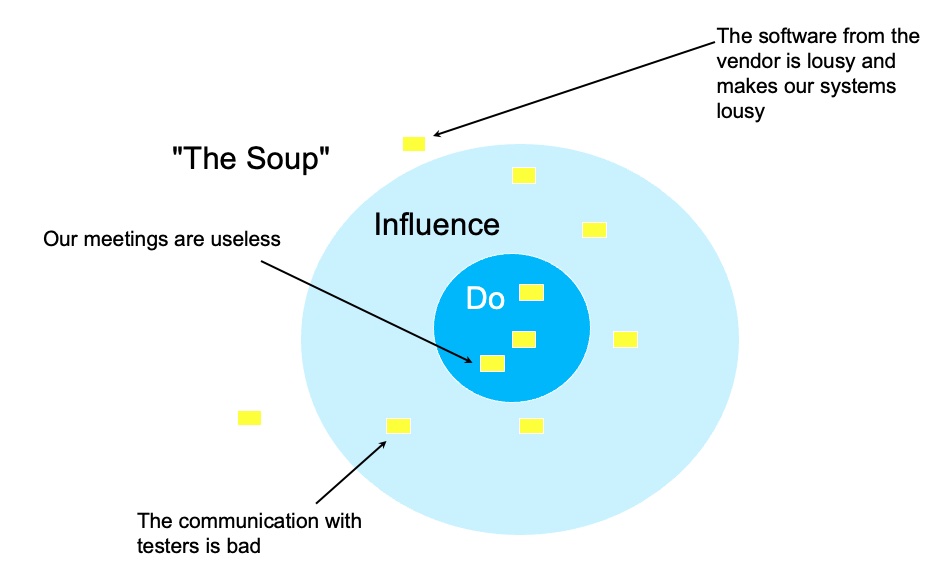

In the Soup

At the next retrospective another antipattern showed up. The team

wanted to discuss the impact of the lousy software their vendors

provided them with. The quality of this was a constant problem

for the team. Their own software systems were greatly affected

by this, and they had tried to escalate the problem to

management. The team had discussed this before, many times. Every

time they discussed it, they got frustrated and sad and nothing changed.

It made the retrospectives feel like a waste of time, because it was a

waste of time to discuss things they could not change. This is an example

of the antipattern In the Soup.

When you are in the soup, you are spending time on things you cannot

improve. Instead of learning about and improving the issues you are able

to change.

The refactored solution is to use an activity called In the Soup,

where you ask the team to divide the things they are discussing into

things they can do something about, things they can influence, and things

that are in the soup. When things are in the soup, they are a part of life

that you cannot change. Your time is better spent accepting and finding a

way to adapt to the situation. Or changing your situation by removing

yourself from the soup. You can use this activity right after you have

gathered data as shown below. Or you can use it when you decide what to do

in order to not leave the retrospective with action points that are not in

your power to implement.

Figure 1:

Things we can do, things we can influence, things that are in

the soup.

Loudmouth

In this team they now know how to focus their time on the things they

can change, and they have learned how valuable it is to spend time on

generating insights. But they still have one problem. They have a

Loudmouth in the team. In all the discussions in the retrospectives

(and in all other meetings) this loudmouth interrupts and tells long

stories and makes it impossible for other team members to take part. The

facilitator tries to invite other team members to speak up, but things do

not change.

This antipattern is something that is often found, but it is not hard

to solve. The first thing to be aware of is why it is a problem. Some

people might say that if someone has something to say, then they should be

allowed to say it, and I agree. But for a retrospective, the time is set

aside for a team to share, appreciate and learn together. And if only

part of the team is able to do that, the time may be partly wasted.

The refactored solution for a team with a loudmouth is to stay away

from plenary discussions. Instead divide people into smaller groups, or

even pairs, to discuss subjects. You can also introduce more writing and

moving of post-its instead of speaking. It can even be beneficial to talk

to the loudmouth after the retrospective. They might not be aware of the

effect they have on others, and often they are very grateful to learn this

about themselves. I have worked with loudmouths that found it changed more

aspects of their lives to be aware of this tendency. Some people are what

we call “active thinkers”, and they need to talk or do something to think.

Obviously they need to be loud when they are thinking, but there is no

harm meant by it.

In this article you have been introduced to three of the most common

antipatterns in retrospective facilitation, and you now have some

tips and tricks on how to avoid to be stuck in one of them. But

remember that the most important skill a facilitator can have is

not to know a lot of activities by

heart, but to listen, to use their intellect to de-escalate conflict

and to continue to reflect and learn what works

for them.